Is the UK mortgage market ‘closed’?

There has been widespread coverage over the past 24 hours of UK mortgage lenders pulling products from the market. Understandably these headlines have sparked some confusion as to why banks and other lenders have been pulling their products, and in turn fuelled growing concerns about the UK’s economic prospects.

To be clear, these moves do not reflect any fundamental weakness in the UK banking sector. UK banks remain both well capitalised and strongly regulated, with the Bank of England’s

prudent use

of the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) and the strict composition of its annual stress tests (the 2022 scenario

was published

on Monday) being two examples of this.

There is a far simpler explanation – the banks have acute uncertainty on the cost of hedging.

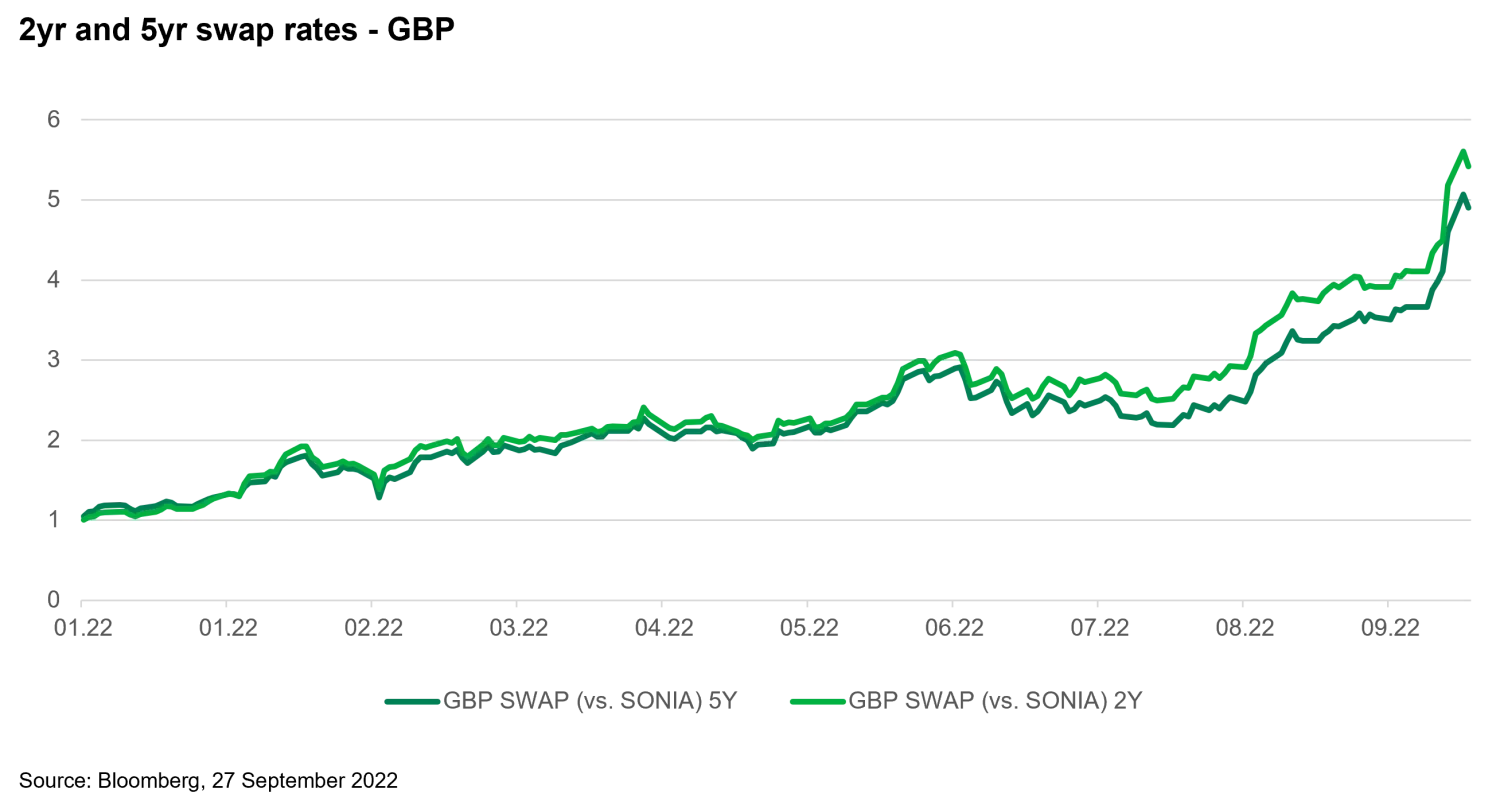

Global central banks’ increasingly determined efforts to combat inflation have resulted in increasingly large moves in their policy rates, leading to some of the most intense moves in government bond yields we have witnessed since the 1970s. These moves are also highly correlated to swap costs (as a reminder, swaps are what banks use to fund themselves with floating rate borrowing but lend to consumers at fixed rates).

The cost of funding and swaps dictate the rates at which mortgage lenders can offer products to consumers; modest moves in either can be absorbed into a lender’s net interest margin (its profit on each product sold) but moves of the magnitude we have seen in the wake of the UK government’s ‘mini Budget’ on Thursday are much harder to absorb.

If you observe the trajectory of swap rates in 2022 for the UK’s most popular fixed rate mortgage products – two- and five-year fixed terms – it’s logical that product rates have also moved briskly upwards throughout the year.

What we saw on Friday and into this week, however, has been such violent moves in swap rates that banks simply do not have sufficient certainty or time to hedge their loan production, which they need to do in order to reverse engineer the rate they should charge on products. A 1% move in two trading days makes it almost impossible for lenders to launch and maintain rates, so as a result we have seen them pull their current products and pause to await more clarity.

This should not cause panic, as UK (and global) banks are liquid, well capitalised and therefore both willing and able to lend. In other words they are capable of fulfilling their critical role in a functioning economy. We also do not expect a wholesale change in lenders’ risk appetite in the short term as a response to fiscal policy, though a measured tightening in lending criteria is a natural response to inflationary environments and has been underway already.

What lenders need is a short period of stability in swaps allowing them to reprice and relaunch their mortgage products, albeit at materially higher rates than those we saw at the start of last week.