Should We Fear the Repo Men?

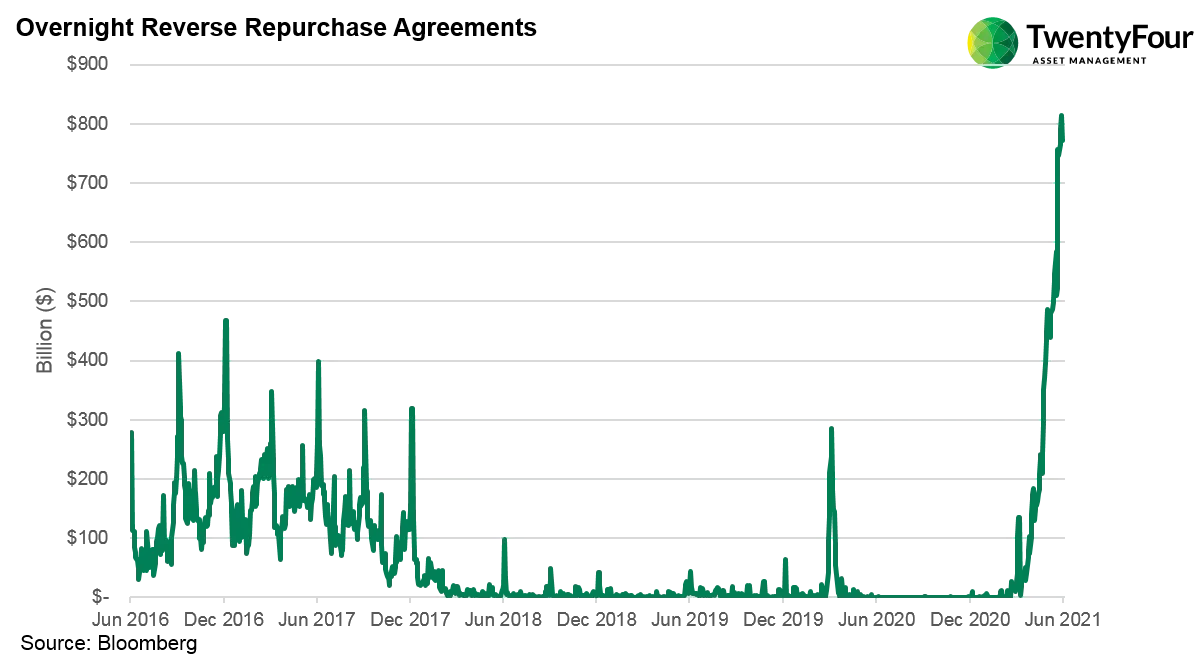

While the global financial crisis made home and vehicle repossessions infamous, COVID-19 has led to a different kind of repo making headlines. Having grown rapidly this year, last week ‘reverse repo’ volumes in the US reached a new high of $813bn. The size of the US Federal Reserve’s Reverse Repurchase Agreement Operations is just one of many large numbers that have been attracting headlines in recent weeks, but having received a number of client enquiries into this development we felt it was worth exploring in more detail.

Reserve repos are overnight operations conducted by the Fed, whereby it sells US Treasuries to financial institutions with an attached agreement to buy them back the next day at a specified, slightly higher price. In effect, financial institutions are making overnight loans to the Fed, backed by US Treasuries, and receiving a positive rate of interest on these loans.

What are these repos for? Essentially, the Fed is keen to reduce cash balances in the banking system to avoid any overnight rate from going negative. The repo operations soak up some of the excess liquidity currently overwhelming US money market funds, which have been flooded with cash this year sending their total holdings above $4tr. The simple explanation for this growth in liquidity is to point at the huge amount of government stimulus undertaken since the arrival of COVID-19, but the most interesting findings come from looking at the timing of this stimulus.

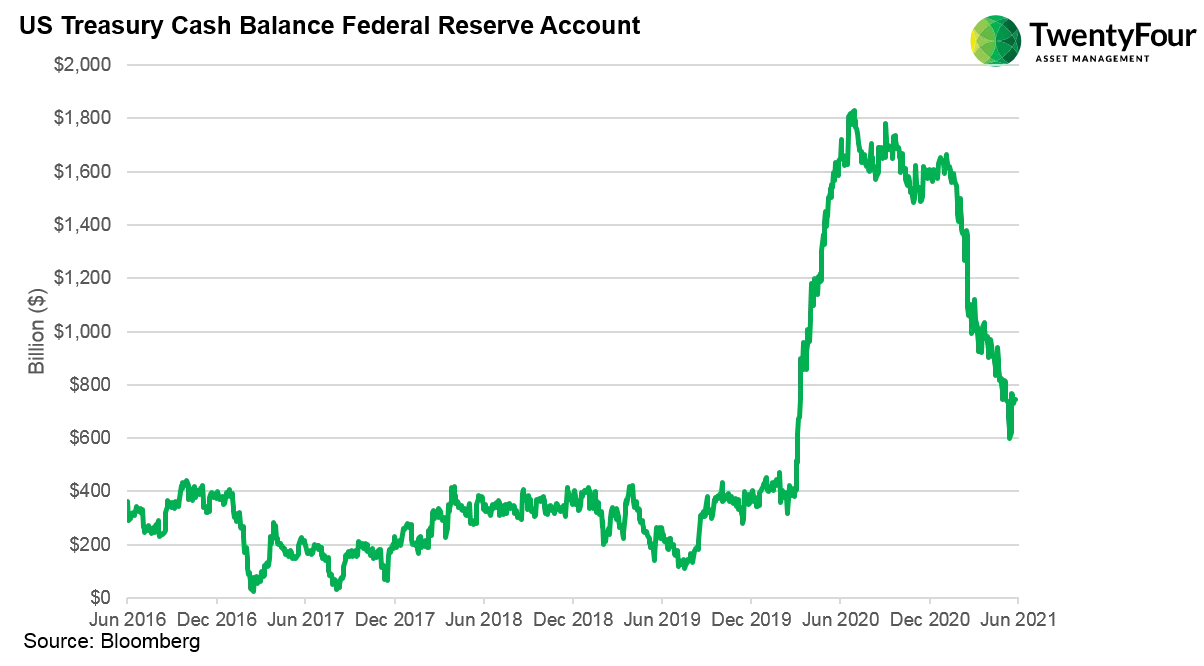

Below is a chart of the US Treasury’s cash balances held at the Federal Reserve. This account holds cash from the sale of Treasury debt issuance and tax receipts collected. In the chart below, we can see the balance as relatively stable with some seasonal fluctuations for the first four years shown. In April 2020, as Congress was signing the CARES Act stimulus bill into law, the Treasury began ramping up issuance of US Treasury bills in anticipation of the spending that would follow. Cash flowed into the Treasury’s account quickly, but stimulus spending did not happen immediately. So the lag we see is partly down to politics (some stimulus was only fully approved in December 2020) and partly down to the time it takes to enact plans and pay providers. However, now that cash is finally being spent by the government, the Treasury’s cash balance is falling – it is down around $1tr from the peak and $750bn year-to-date. That cash ultimately ends up in the commercial bank accounts of the companies and individuals who have received it.

Again, on a temporary but rolling basis, reverse repos take cash out of the banking system. Thus when we look at Fed repo volumes in the chart below, we can see the growth of volumes arrives in line with the fall in Treasury balances.

Excess liquidity in money market funds has been one of the technical factors holding US Treasury yields low despite the threat of non-transitory inflation, since those funds have to be invested somewhere. Ultimately the Fed is aiming to maintain a balance here by reducing that liquidity, and so further growth in the usage of reverse repos is not necessarily a danger sign. The Fed will be able to reduce the size of its operations once the Treasury cash spend slows.

However, given the magnitude of the amounts involved we do think there is potential for some temporary volatility in the US Treasury market as the volumes change. We will be keeping a keen eye on both in the months ahead.