Fixed vs. Floating: Where’s The Yield?

One of the most fundamental decisions a fixed income investor can make is on the type of interest rate risk they want to take.

Those that opt for primarily fixed rate exposure tend to be focused on the extra yield that is typically provided by an upward sloping yield curve; why would you want a floating rate bond whose yield is driven by a variable three-month rate, the argument goes, if you are well compensated for taking longer fixed rate risk further along the curve?

Yield isn’t the only consideration, of course (there are often good reasons for buying floating rate bonds, near-zero interest rate risk being one of them) but in the post-COVID world of massive central bank support and flattened government bond curves the fixed vs. floating dilemma is now a lot less clear cut.

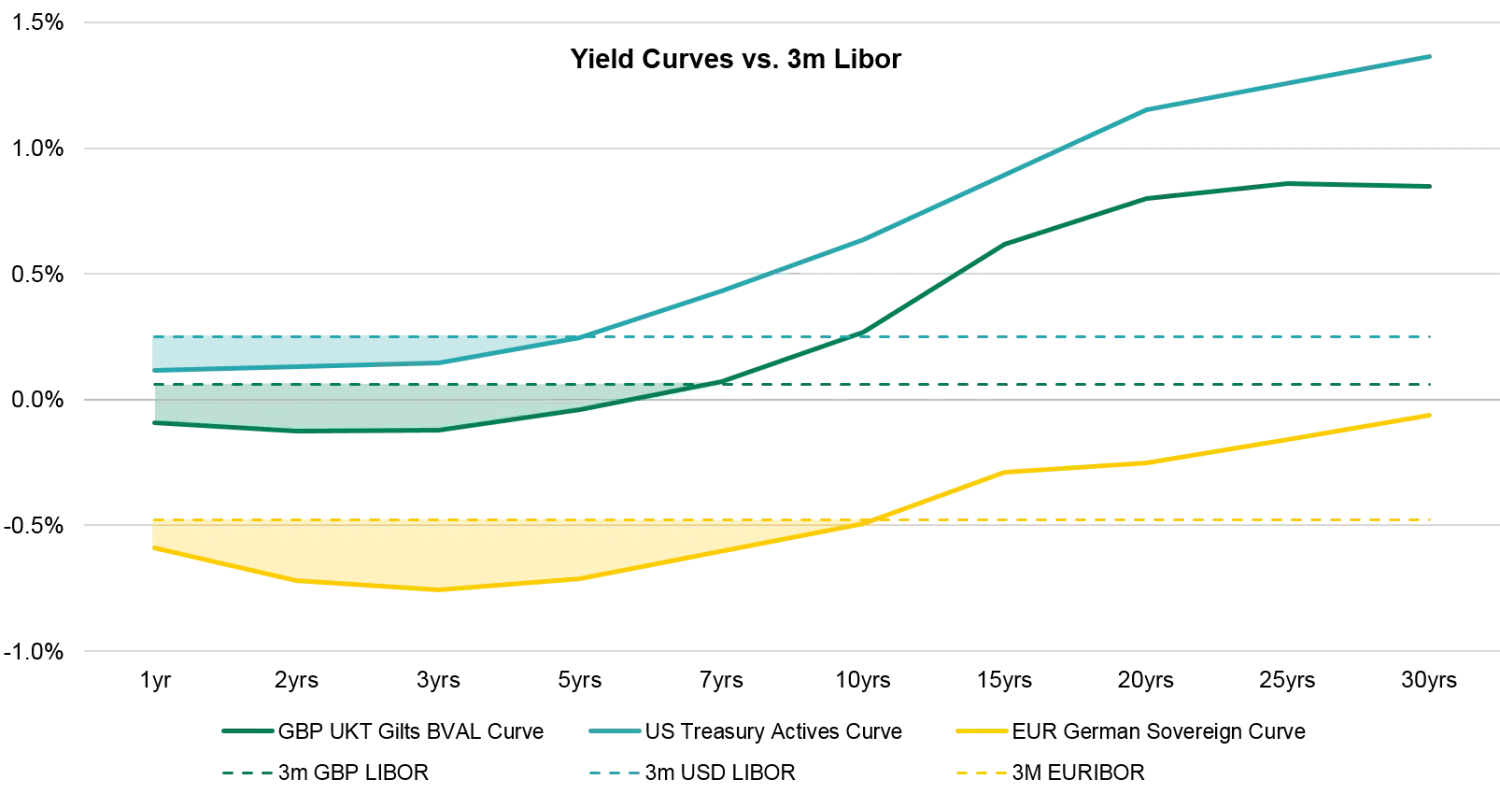

Why? Have a look at the graph below.

The rates curves in all the major currencies now yield less than the main floating rate indices, all the way along the curve until you get to either five or seven years, and even then the pick-up is less than head-turning. What used to be a handsome pick-up on fixed rate risk can now actually cost you some yield, depending on which curve and which point you are looking at.

This is no different from pre-COVID, using Gilts as an example, where the three-month Libor rate still looked attractive versus the Gilt curve. However, back in those heady days of a 50bp to 60bp yield at the five-year point, there was still room for the curve to drop and for fixed rate bond investors to clip capital gains. That trade has largely happened, and for it to happen again one of two things would have to happen. Either interest rates would have to go up before they go down (with painful consequences for bond prices), or the curve would have to move even lower from here. In the UK and the US, the central banks are perfectly aware that the latter would represent an effective brake on bank earnings, so while they haven’t explicitly ruled this out, the Eurozone’s experience shows a materially more negative yield curve comes with negative consequences and should be a last resort.

Will the rates curve ever get back to more familiar steepness? Maybe, but probably not in the next couple of years, and when it does occur it will be a hard experience for investors, unwinding all the upside the compression of the curve has provided in the past.

So what does this mean for bond buyers?

We believe investors looking for income today are only going to get that from the credit spread on bonds, rather than from either the index or the point on the yield curve where they are investing. Essentially, income from the rates curve has become worthless, and if anything can create more risk for little or no reward.

If floating vs. fixed is no longer the most pressing question, then investors should be more focused on where they get the best credit spread. Despite the relentless rally in risk assets since the COVID-related panic in March and April, there are still pockets of the bond market where we believe investors are better compensated by credit spread, whether that is in fixed rate notes such as AT1s, or floating rate options such as ABS and CLOs.